On his 1875-1876 winter journey to Khiva (now a city in Uzbekistan), British explorer Fred Burnaby encounters the Kirghiz, the Muslim nomads of Central Asia.

The Kirghiz have a custom of betrothing their sons to girls often several years before the latter have arrived at puberty. This is done by the parents of the interested parties, the father of the lad giving so many of the flock to the girl’s parents. When the lady is old enough, the bridegroom fetches her home to his habitation. Her father, if he be generous, returns to the young couple the same number of animals that he has previously received, with a few in addition as interest. But this is only among the more wealthy families; the heads of poorer establishments do not feel inclined to give back any of their sheep. They prefer being thought stingy to having nothing to subsist upon during the winter.

Sometimes the matrimonial arrangement is made by the would-be husband, who, going straight to the girl’s parents, strikes a bargain with them for their daughter. When all things are arranged, he returns alone to his own kibitka, which is, perhaps, two or three hundred versts from the young lady’s home. After waiting here a few days he goes back for his bride. It is considered a sign of manhood that the bridegroom should—regardless of robbers and marauding parties—bring no companions when journeying towards the kibitka of his betrothed. The young lady herself sits inside the tent, and sings a ditty which has reference to her lover’s bravery, to her own good looks, and to his good fortune, to sheep, and to the festivities about to ensue.

The women of the tribe squat on the ground and form a circle round the tent. If the bridegroom attempts to enter the bride’s kibitka, the jealous females rush forward and beat him with sticks, the most unfavoured and elderly of the unmarried women taking great delight in this performance. However, love generally prevails; the young man’s back smarts, but he forces a passage into the kibitka. His beloved one now throws herself into his arms, and he soon finds a solace for his troubles. The young lady then presents him with some feathers, red silk, and cloves, this being the accustomed offering made by a Kirghiz maiden to her bridegroom to testify to him her purity and affection. The happy couple are now left alone, the women outside singing some native ditty, in which the joys of marriage are rather forcibly described.

Feasting then begins. Friends and relations come from all parts of the steppe, having brought horses and sheep as a contribution to the festival; indeed, without this it would be impossible for the host to give the entertainment, for he would be literally eaten out of house and home. Sometimes a hundred sheep and forty or fifty horses are slain, the iron cauldron being kept all day long at boiling point. The Kirghiz stuff themselves to repletion, and afterwards carry away in their trousers, which they tie up at the knee, the meat they are unable to swallow at the time. It is a peculiar pocket, the roast mutton in this manner coming closely in contact with the Kirghiz legs; but such little matters do not affect these half wild wanderers.

When the feast is over the games begin. The animals which have not been killed are set apart as prizes, the young men wrestling with each other; no tripping is allowed, no dexterity comes into play, and the contest is decided by sheer strength. After this there are horse races, the length of the course being from twenty to thirty miles, this distance being accomplished at the rate of from eighteen to twenty miles an hour. The successful rider sometimes receiving eight or nine horses as a prize.

Then the girls mount the swiftest horses, which they can borrow from their friends or relations. One of the Amazons challenging the men to race against her gallops across the steppe. She is pursued by a horseman, who strives to place his hand round her waist. The girl all this time showers blows with her whip on the head of her admirer, and does her best to keep him at bay. If he does not succeed in his attempt, she will turn round upon him, and so belabour the unfortunate wight with her whip that he frequently falls off his horse. He is then an object of scorn and derision to all the assembled guests. But if, on the contrary, he succeeds in placing his hand on the girl’s breast, she surrenders at once, and they ride away together amid the cheers and encouraging shouts of the company. It is not considered strict etiquette to follow, as chaperons in Tartary are not considered necessary.

The Turkomans sometimes decide the knotty point of who is to marry the prettiest girl in their tribe in the same primitive manner. On these occasions the whole tribe turns out, and the young lady, being allowed her choice of horses, gallops away from her suitors. They follow her. She avoids those whom she dislikes, and seeks to throw herself in the way of the object of her affections. The moment that she is caught, she becomes the wife of her captor. Further ceremonies are dispensed with, and he takes her to his tent.

“What do you pay in your country for a wife?” asked the guide, when I had finished questioning him on these subjects.

“We pay nothing; we ask the girl, and if she says yes, and her parents do not refuse, we marry her.”

“But, if the girl does not like you, if she hits you on the head with her whip, or gallops away when you ride up to her side, what do you do in that case?”

“Why, we do not marry her.”

“But if you want to marry her very much; if you love her more than your best horse and all your sheep and camels put together?”

“We cannot marry her without her consent.”

“And are the girls moon-faced?”

“Some of them.”

The guide appeared to be lost in a fit of meditation very unusual amidst the Arabs of the steppes. Presently, removing his sheepskin hat, and rubbing his closely shaven head, he said, “Will you take me with you to your country? It would be so nice; I should get a moon-faced wife, and all for nothing. Why, she would not cost so much as a sheep.”

“But supposing she would not have you?”

“Not have me!” and the guide here looked at me in astonishment, which he emphasised in a manner peculiar to his countrymen, by using his fingers instead of a pocket-handkerchief. “Not have me! Well, I should give her a white wrapper, or a ring for her ears or her nose.”

“And if she still refused you?”

“Why, I would give her a gold ornament for her head; and what girl is there who could resist such a present?”

From A Ride to Khiva by Fred Burnaby*

Follow Classic Travel Tales on Facebook.

Read More Classic Travel Tales.

New material and editing © 2025 L.A. Mulnix, Publisher.

*L.A. Mulnix, Publisher, participates in the Amazon Associates program, which pays us a small commission on qualified purchases.

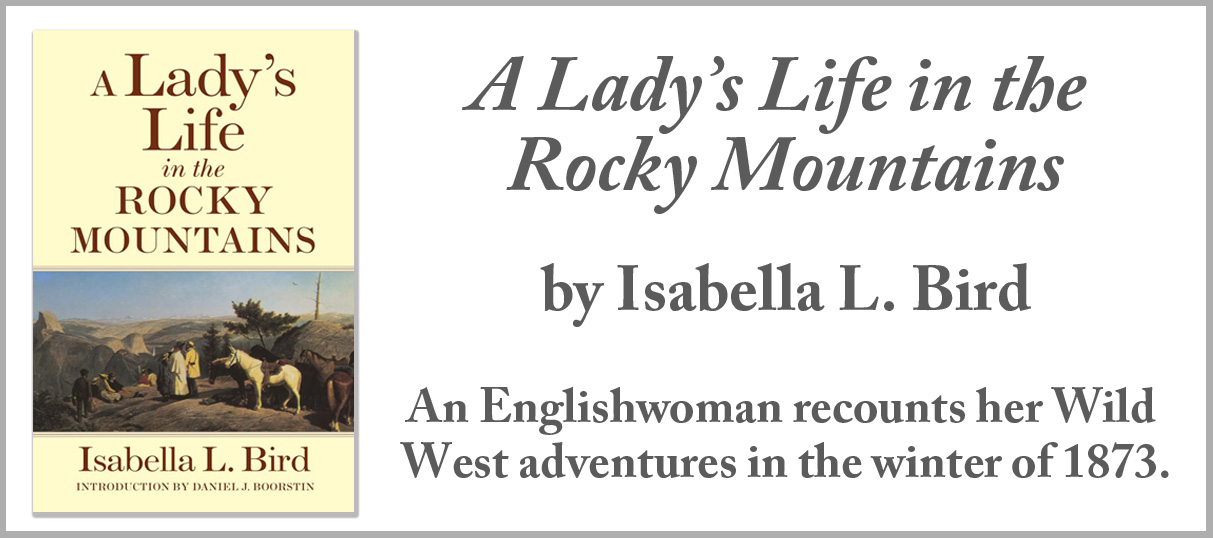

Image: Inside the Tent of a Rich Kirghiz by Vasily Vereshchagin, 1869/1870, Tretyakov Gallery, public domain.